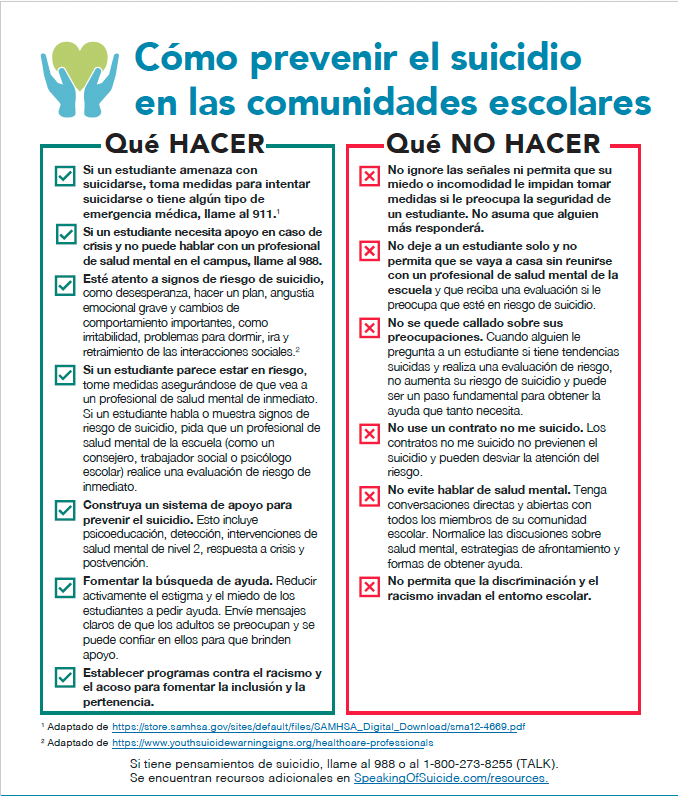

Español

5 cosas que todos en las escuelas deberían saber acerca de la prevención del suicidio

(Este recurso fue publicado en ingles por Student Behavior Blog. El programa de Student Behavior (basado en SRI Education) promueve y evalúa estrategias basadas en la investigación para apoyar la salud mental, el comportamiento positivo y el bienestar de los niños.)

Mayo 2023

De Daniel Cohen

Con el surgimiento de la pandemia de COVID-19, hemos visto un aumento significativo en los síntomas de problemas de salud mental entre los jóvenes en edad escolar. En particular, el porcentaje de niños con síntomas de depresión y ansiedad se ha vuelto mucho mayor.1 También ha habido una gran preocupación sobre el potencial de un aumento en el comportamiento suicida de los jóvenes relacionado con la pandemia, aunque la investigación es mixta con algunos datos. no muestran aumentos2 y otros presentan datos que sugieren que, al menos en algunos subgrupos y ubicaciones, el riesgo de suicidio ha aumentado. Por ejemplo, hay evidencia de un aumento en las visitas al departamento de emergencias asociadas con intentos de suicidio en niñas,3 y aumentos a nivel estatal en el suicidio de adolescentes en algunas regiones de los EE. UU.4

En conjunto, los impactos de la pandemia en el suicidio juvenil son complejos, ya que algunos grupos han experimentado niveles más altos de pensamientos y comportamientos suicidas, y todos los niños corren el riesgo de sufrir un aumento significativo de los factores de riesgo de salud mental. A medida que salimos del trauma colectivo de la pandemia y trabajamos para ayudar a los jóvenes en el contexto de un patrón de una década de aumento del riesgo de suicidio,5 es crucial que todos los que pasan tiempo en las escuelas (incluidos los padres) estén al tanto de estos hechos clave relacionados con la prevención del suicidio juvenil.

1. Preguntar a los estudiantes si tienen tendencias suicidas NO aumenta su riesgo

A pesar de la creencia común de que preguntarles a los niños si tienen tendencias suicidas aumentará el riesgo, las investigaciones nos dicen que cuando se les pregunta a las personas si tienen tendencias suicidas, no empeoran sus síntomas ni aumenta el riesgo de intentarlo.6 De hecho, muchos estudios muestran que preguntar sobre el riesgo reduce la probabilidad de futuros pensamientos y comportamientos suicidas.6 Además, la evaluación del riesgo nos permite brindarle a alguien la ayuda que necesita.

Si un estudiante muestra signos de riesgo de suicidio, como desesperanza, hacer un plan, angustia emocional grave y cambios de comportamiento importantes, como irritabilidad, problemas para dormir, ira y de las interacciones sociales7, es esencial que vea a un proveedor de salud mental y recibir una evaluación de riesgos lo antes posible. Esto lo puede hacer un profesional de salud mental de la escuela, como un consejero, un trabajador social o un psicólogo escolar. No deje a un estudiante solo y no permita que se vaya a casa sin reunirse con un profesional de salud mental de la escuela y recibir una evaluación si le preocupa que esté en riesgo de suicidio.

Si cree que un estudiante está en riesgo inmediato de suicidio, está amenazando con suicidarse, está tomando medidas para intentar suicidarse o tiene algún tipo de emergencia médica, llame al 911.8 Si un estudiante necesita apoyo en caso de crisis y no puede hablar con un profesional de salud mental en el campus, llame al 988 (solo disponible en los EE.UU.).

2. Los contratos “no me suicido” NO funcionan y NO reducirán el riesgo de suicidio

Un contrato de no me suicido es un documento que un profesional de salud mental de la escuela u otro miembro del personal de la escuela puede pedirle a un estudiante que firme si está en riesgo de suicidio. Al firmar el contrato, un estudiante acepta que no se dañará a sí mismo. Si bien este enfoque tiene buenas intenciones, las investigaciónes nos dicen claramente que los contratos no me suicido no previenen el suicidio.9 De hecho, el uso de esta práctica puede ser perjudicial porque el personal escolar que la utiliza puede creer que han utilizado una estrategia eficaz y se están protegiendo a sí mismos de la responsabilidad cuando ninguna conclusión es correcta. Cualquier tiempo que se dedique a usar estrategias ineficaces es tiempo perdido al emplear intervenciones que funcionan.

3. Las creencias y normas sociales acerca de pedir ayuda hacen la diferencia

Los estudiantes que pierden a un amigo cercano o a un pariente por suicidio tienen más probabilidades de estar en riesgo.10 Una explicación clave para el hallazgo de esta investigación es que cuando alguien ve ejemplos de compañeros cercanos y respetados que mueren por suicidio, es más probable que lo vean como una respuesta adecuada a las circunstancias desafiantes, o como señalaron varios investigadores en su trabajo sobre redes sociales y grupos de suicidios de adolescentes, “las historias que contamos sobre el suicidio son importantes para ver si el suicidio se ve como una opción”.11 Al enviar mensajes claros a los estudiantes de que la búsqueda de ayuda se acepta, es normal y se alienta, y que se puede confiar en los adultos para que brinden apoyo, las escuelas pueden promover la idea de que las situaciones difíciles pueden mejorar si los estudiantes piden ayuda. Esto puede ser un desafío porque a menudo existe una tendencia a evitar hablar sobre la salud mental por temor a incomodar a los demás, crear una carga o preocupaciones de que los problemas empeoren al hablar sobre ellos. Los esfuerzos para crear creencias positivas acerca de cómo obtener ayuda y reforzar la percepción de que los adultos son afectuosos y confiables pueden desempeñar un papel importante en la prevención del suicidio.

4. La discriminación es un factor de riesgo extremadamente importante pero poco reconocido para el suicidio.

La discriminación es una experiencia común en los Estados Unidos, y la mayoría de los estadounidenses la reconocen como un problema generalizado.12 A menudo vemos el acoso y la desconexión social como factores de riesgo importantes para el suicidio, pero es posible que no todos piensen que la discriminación es un problema especial y muy importante fuente de la intimidación, el aislamiento social y el rechazo. Además, es importante tener en cuenta que la discriminación ocurre en el contexto de una variedad de identidades, incluidas la raza, el origen étnico, la orientación sexual, la identidad de género y la nacionalidad, por nombrar solo algunas, pero esta no es una lista exhaustiva.

Varios estudios destacan el impacto de la discriminación en las tendencias suicidas. Por ejemplo, las investigaciones ha encontrado que cuando los adolescentes experimentan discriminación relacionada con su raza y etnia, es más probable que tengan pensamientos suicidas.13 También hay evidencia de que los jóvenes de minorías sexuales y de género que enfrentan discriminación tienen más probabilidades de tener pensamientos y comportamientos suicidas.14 En última instancia, es fundamental reconocer que cualquier esfuerzo por prevenir la discriminación en la escuela puede reducir el riesgo de suicidio para los estudiantes marginados.

5. Podemos prevenir el suicidio dando a los estudiantes acceso a tratamientos y programas eficaces.

Nosotros podemos prevenir el suicidio. Es la segunda causa principal de muerte en niños de 10 a 19 años, pero existen tratamientos efectivos que pueden salvar vidas. Por ejemplo, dos grandes estudios han demostrado que un tipo de psicoterapia llamada Terapia conductual dialéctica (DBT) reduce los intentos de suicidio en adolescentes de alto riesgo.15 Otro ejemplo es un programa global llamado Jóvenes conscientes de la salud mental (YAM) que incluye sesiones grupales que se imparten en la escuela de la misma manera que se ofrecen los programas de educación para la salud y proporciona información sobre los desafíos de la salud mental y los factores de riesgo y de protección. Los investigadores han descubierto que YAM reduce los pensamientos y comportamientos suicidas.16

Sin embargo, la existencia de tratamientos efectivos no es suficiente para prevenir el suicidio; las escuelas deben usarlos y hacerlos accesibles para todos. El uso generalizado de prácticas ineficaces como los contratos “no me suicido” muestra que la selección de programas eficaces no es un hecho. Los líderes escolares deben confiar en los miembros del personal que tienen conocimientos sobre la prevención y los recursos del suicidio desarollados por expertos (p.ej., La Política del Distrito Escolar Modelo sobre la Prevención del Suicidio [inglés]) para seleccionar prácticas y tratamientos que funcionan. Además, las escuelas y los distritos deben abordar las barreras para el acceso y el uso de los servicios, como el estigma y la dotación de personal inadecuada.

Descargar e imprimir:

Cómo prevenir el suicidio en las comunidades escolares

Si tiene pensamientos de suicidio, llame al 988 o al 1-800-273-8255 (TALK) (solo en los EE.UU.). Se encuentran recursos adicionales en SpeakingOfSuicide.com/resources.

Referencias

1 Racine, N., Cooke, J. E., Eirich, R., Korczak, D. J., McArthur, B., & Madigan, S. (2020). Child and adolescent mental illness during COVID-19: A rapid review. Psychiatry Research, 292, 113307.

2Ehlman, D. C., Yard, E., Stone, D. M., Jones, C. M., & Mack, K. A. (2022). Changes in Suicide Rates-United States, 2019 and 2020. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 71(8), 306-312.

3Yard, E., Radhakrishnan, L., Ballesteros, M. F., Sheppard, M., Gates, A., Stein, Z., … & Stone, D. M. (2021). Emergency department visits for suspected suicide attempts among persons aged 12–25 years before and during the COVID-19 pandemic—United States, January 2019–May 2021. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 70(24), 888.

4Charpignon, M. L., Ontiveros, J., Sundaresan, S., Puri, A., Chandra, J., Mandl, K. D., & Majumder, M. S. (2022). Evaluation of suicides among US adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Pediatrics.

5Curtin, S. C., & Heron, M. P. (2019). Death rates due to suicide and homicide among persons aged 10–24: United States,2000–2017. Retrieved from Hyattsville, MD

6Blades, C. A., Stritzke, W. G., Page, A. C., & Brown, J. D. (2018). The benefits and risks of asking research participants about suicide: A meta-analysis of the impact of exposure to suicide-related content. Clinical Psychology Review, 64, 1-12.

7https://www.youthsuicidewarningsigns.org/healthcare-professionals

8https://store.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/SAMHSA_Digital_Download/sma12-4669.pdf

9Lewis, L. M. (2007). No‐harm contracts: A review of what we know. Suicide and Life‐Threatening Behavior, 37(1), 50-57.

10Maple, M., Cerel, J., Sanford, R., Pearce, T., & Jordan, J. (2017). Is exposure to suicide beyond kin associated with risk for suicidal behavior? A systematic review of the evidence. Suicide and Life‐Threatening Behavior, 47(4), 461-474.

11Abrutyn, S., Mueller, A. S., & Osborne, M. (2020). Rekeying cultural scripts for youth suicide: How social networks facilitate suicide diffusion and suicide clusters following exposure to suicide. Society and Mental Health, 10(2), 112-135.

12https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2021/03/18/majorities-of-americans-see-at-least-some-discrimination-against-black-hispanic-and-asian-people-in-the-u-s/

13Polanco-Roman, L., DeLapp, R. C., Dackis, M. N., Ebrahimi, C. T., Mafnas, K. S., Gabbay, V., & Pimentel, S. S. (2022). Racial/ethnic discrimination and suicide-related risk in a treatment-seeking group of ethnoracially minoritized adolescents. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 13591045221132682.

14Wyman Battalen, A., Mereish, E., Putney, J., Sellers, C. M., Gushwa, M., & McManama O’Brien, K. H. (2021). Associations of discrimination, suicide ideation severity and attempts, and depressive symptoms among sexual and gender minority youth. Crisis: The Journal of Crisis Intervention and Suicide Prevention, 42(4), 301.

15McCauley, E., Berk, M. S., Asarnow, J. R., Adrian, M., Cohen, J., Korslund, K., … & Linehan, M. M. (2018). Efficacy of dialectical behavior therapy for adolescents at high risk for suicide: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry, 75(8), 777-785.

16Wasserman, D., Hoven, C. W., Wasserman, C., Wall, M., Eisenberg, R., Hadlaczky, G., … & Carli, V. (2015). School-based suicide prevention programmes: the SEYLE cluster-randomised, controlled trial. The Lancet, 385(9977), 1536-1544.

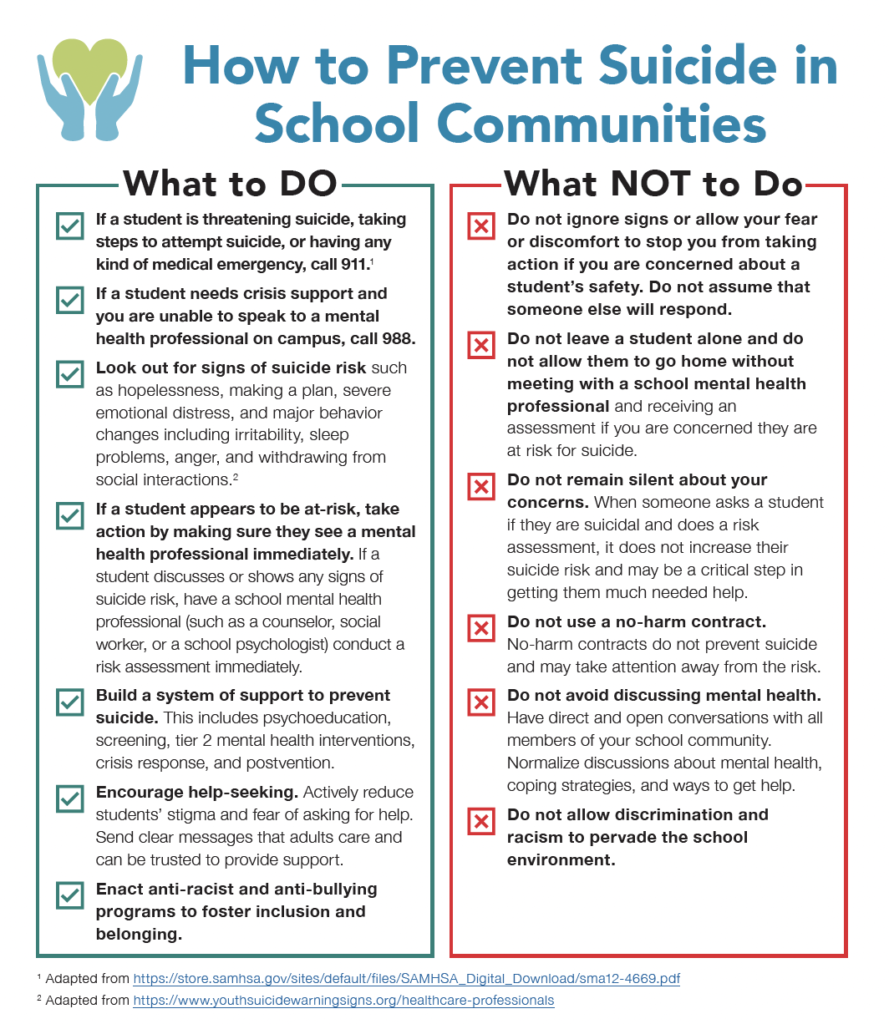

English

5 Things that Everyone in Schools Should Know about Suicide Prevention

(Repost of a December 2022, post on the Student Behavior Blog. The Student Behavior Blog at SRI Education provides the latest information about evidence-based approaches to support all students’ positive behavior, mental health, and well-being. )

May 2023

By Daniel Cohen

With the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic, we have seen a significant increase in symptoms of mental health problems among school-aged youth. Most notably, the percentage of children with symptoms of depression and anxiety has become much larger.1 There has also been a great deal of concern about the potential for a pandemic-related increase in youth suicidal behavior, but the research is mixed with some data showing no increases2 and others presenting data suggesting that at least in some subgroups and locations, suicide risk has increased. For example, there is evidence for an increase in emergency department visits associated with suicide attempts in girls,3 and state-level increases in adolescent suicide in some regions of the US.4

Taken together, the impacts of the pandemic on youth suicide are complex with some groups having experienced greater levels of suicidal thoughts and behavior, and all children at risk for significant increases in mental health risk factors. As we emerge from the collective trauma of the pandemic and work to serve youth in the context of a decade long pattern of increasing in suicide risk,5 it is crucial that everyone who spends time in schools (including parents) is aware of these key facts related to youth suicide prevention.

1. Asking students if they are suicidal does NOT increase their risk

In spite of the commonly held belief that asking kids if they are suicidal will increase risk, research tells us that when people are asked if they are suicidal, it does not worsen their symptoms or increase their risk of making an attempt.6 In fact, many studies show that asking about risk reduces the likelihood of future suicidal thoughts and behaviors.6 In addition, risk assessment allows us to get someone the help they need.

If a student shows any signs of suicide risk, such as hopelessness, making a plan, severe emotional distress, and major behavior changes including, irritability, sleep problems, anger, and withdrawing from social interactions7 it is essential that they see a mental health provider and receive a risk assessment as soon as possible. This can be done by a school mental health professional such as a counselor, social worker, or school psychologist. Do not leave a student alone and do not allow them to go home without meeting with a school mental health professional and receiving an assessment if you are concerned they are at risk for suicide.

If you believe that a student is at immediate risk for suicide, is threatening suicide, taking steps to attempt suicide, or having any kind of medical emergency call 911.8 If a student needs crisis support and you are unable to speak to a mental health professional on campus, call 988.

2. “No-Harm” contracts do NOT work and will NOT decrease suicide risk

A no-harm contract is a document that a school mental health professional or other school staff member may ask a student to sign if they are at-risk for suicide. By signing the contract, a student agrees that they will not harm themselves. While this approach is well intentioned, research tells us very clearly no-harm contracts do not prevent suicide.9 In fact, the use of this practice can be harmful because school staff using it may believe they have used an effective strategy and are protecting themselves from liability where neither conclusion is correct. Any time spent using ineffective strategies is time lost employing interventions that work.

3. Beliefs and social norms about asking for help make a difference

Students who lose a close friend or relative to suicide are more likely to be at risk.10 A key explanation for this research finding is that when someone sees examples of close and respected peers dying by suicide, they are more likely to view it as an appropriate response to challenging circumstances, or as several researchers noted in their work on social networks and adolescent suicide clusters, “the stories we tell about suicide matter to whether suicide is seen as an option.”11 By sending clear messages to students that help-seeking is accepted, normal, and encouraged, and that adults can be trusted to provide support, schools can promote the idea that difficult situations can get better if students ask for help. This can be challenging because there is often a tendency to avoid discussing mental health for fear of making others uncomfortable, creating a burden, and or concerns that problems will be made worse by talking about them. Efforts that to create positive beliefs about getting help and reinforcing the perception that adults are caring and trustworthy can play in important role in suicide prevention.

4. Discrimination is an extremely important but underrecognized risk factor for suicide.

Discrimination is a common experience in the United States, with most Americans recognizing it as a widespread problem.12 We often see bullying and social disconnection as important risk factors for suicide, but it may not occur to everyone that discrimination is a special, highly important source bullying, social isolation, and rejection. Further it is important to be aware that discrimination occurs in the context of a variety of identities including race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, gender identity, and nationality to name just a few, but this is not an exhaustive list.

Several studies highlight the impact of discrimination on suicidality. For example, research has found that when adolescents experience discrimination related to their race and ethnicity, they are more likely to have suicidal thoughts.13 There is also evidence that sexual and gender minority youth who encounter discrimination are more likely to have suicidal thoughts and behaviors.14 Ultimately, it critical to recognize that any efforts to prevent discrimination at school can reduce suicide risk for marginalized students.

5. We can prevent suicide by giving students access to effective treatments and programs.

We can prevent suicide. It is the second leading cause of death in children 10-19, but there are effective treatments that can save lives. For example, two large studies have demonstrated that at type of psychotherapy called Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT) reduces suicide attempts in high-risk adolescents.15 Another example is a universal program called Youth Aware of Mental Health (YAM) involving group sessions that are delivered at school in the same way that health education programs are offered and provides information about mental health challenges, and risk and protective factors. Researchers have found that YAM reduces suicidal thoughts and behavior.16

However, the existence of effective treatments is not enough to prevent suicide; schools must use them and make them accessible to everyone. The widespread use of ineffective practices such as “no-harm” contracts shows that the selection of effective programs is not a given. School leaders must rely on staff members who are knowledgeable about suicide prevention and resources developed by experts (e.g., The Model School District Policy on Suicide Prevention) to select practices and treatments that work. In addition, schools and districts must address barriers to access and service use such as stigma and inadequate staffing.

Download and print:

How to Prevent Suicide in School Communities

If you are having thoughts of suicide, call 988 or 1-800-273-8255 (TALK). Additional resources are located at SpeakingOfSuicide.com/resources.

References

1 Racine, N., Cooke, J. E., Eirich, R., Korczak, D. J., McArthur, B., & Madigan, S. (2020). Child and adolescent mental illness during COVID-19: A rapid review. Psychiatry Research, 292, 113307.

2Ehlman, D. C., Yard, E., Stone, D. M., Jones, C. M., & Mack, K. A. (2022). Changes in Suicide Rates-United States, 2019 and 2020. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 71(8), 306-312.

3Yard, E., Radhakrishnan, L., Ballesteros, M. F., Sheppard, M., Gates, A., Stein, Z., … & Stone, D. M. (2021). Emergency department visits for suspected suicide attempts among persons aged 12–25 years before and during the COVID-19 pandemic—United States, January 2019–May 2021. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 70(24), 888.

4Charpignon, M. L., Ontiveros, J., Sundaresan, S., Puri, A., Chandra, J., Mandl, K. D., & Majumder, M. S. (2022). Evaluation of suicides among US adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Pediatrics.

5Curtin, S. C., & Heron, M. P. (2019). Death rates due to suicide and homicide among persons aged 10–24: United States,2000–2017. Retrieved from Hyattsville, MD

6Blades, C. A., Stritzke, W. G., Page, A. C., & Brown, J. D. (2018). The benefits and risks of asking research participants about suicide: A meta-analysis of the impact of exposure to suicide-related content. Clinical Psychology Review, 64, 1-12.

7https://www.youthsuicidewarningsigns.org/healthcare-professionals

8https://store.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/SAMHSA_Digital_Download/sma12-4669.pdf

9Lewis, L. M. (2007). No‐harm contracts: A review of what we know. Suicide and Life‐Threatening Behavior, 37(1), 50-57.

10Maple, M., Cerel, J., Sanford, R., Pearce, T., & Jordan, J. (2017). Is exposure to suicide beyond kin associated with risk for suicidal behavior? A systematic review of the evidence. Suicide and Life‐Threatening Behavior, 47(4), 461-474.

11Abrutyn, S., Mueller, A. S., & Osborne, M. (2020). Rekeying cultural scripts for youth suicide: How social networks facilitate suicide diffusion and suicide clusters following exposure to suicide. Society and Mental Health, 10(2), 112-135.

12https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2021/03/18/majorities-of-americans-see-at-least-some-discrimination-against-black-hispanic-and-asian-people-in-the-u-s/

13Polanco-Roman, L., DeLapp, R. C., Dackis, M. N., Ebrahimi, C. T., Mafnas, K. S., Gabbay, V., & Pimentel, S. S. (2022). Racial/ethnic discrimination and suicide-related risk in a treatment-seeking group of ethnoracially minoritized adolescents. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 13591045221132682.

14Wyman Battalen, A., Mereish, E., Putney, J., Sellers, C. M., Gushwa, M., & McManama O’Brien, K. H. (2021). Associations of discrimination, suicide ideation severity and attempts, and depressive symptoms among sexual and gender minority youth. Crisis: The Journal of Crisis Intervention and Suicide Prevention, 42(4), 301.

15McCauley, E., Berk, M. S., Asarnow, J. R., Adrian, M., Cohen, J., Korslund, K., … & Linehan, M. M. (2018). Efficacy of dialectical behavior therapy for adolescents at high risk for suicide: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry, 75(8), 777-785.

16Wasserman, D., Hoven, C. W., Wasserman, C., Wall, M., Eisenberg, R., Hadlaczky, G., … & Carli, V. (2015). School-based suicide prevention programmes: the SEYLE cluster-randomised, controlled trial. The Lancet, 385(9977), 1536-1544.

Tags: Suicide Prevention